Culture for people is a bit like water for fish. Most of us don’t know we have one, although we plainly see cultural biases in those outside our group—biases that stop them from seeing the world as it really is.

Our culture is key to our identity. The group we belong to influences what we perceive as cool or nerdy, de rigueur or verboten. Our brand preferences are very much connected to our culture.

Thriving cultures are built on a solid foundation of shared values, and a steady inflow of new ideas. Stem the flow of ideas, and the culture stagnates. Allow a tidal wave of ideas, and you risk instability.

In an increasingly wired world, it’s nearly impossible to block new ideas from outside. Certainly, oppressive regimes like North Korea’s do their best, but they’re an anomaly. And from the accounts I’ve read, it hasn’t helped them create a terribly healthy, dynamic culture.

The nice thing about today’s technology-driven inflow is that it can be regulated by controlling our screen time. In theory at least, we can absorb new ideas at our own speed, without going catatonic from cognitive overload.

I see tidal waves of “new” that can’t be turned off.

On the horizon, however, I see tidal waves of new that can’t be turned off. They won’t come to us on screens, but in the form of hordes of people from far-off places. The cause of these tidal waves will be migration driven by climate change, and the economic chaos it engenders.

Humans have migrated since, well, forever. We’ve moved for a myriad of reasons—following the seasons, chasing the herds, escaping from one nastiness or another. In short, seeking a better life.

Major migrations triggered by economic, political, and natural disruptions are nothing new, either—think Irish Potato Famine, the Great Depression, and pretty much every major conflict since ancient times. So what makes these new migrations so different?

For one, the numbers are getting bigger.

During the dirty thirties, 2.5 million Americans abandoned their dustbowl farms and headed west.

In 2009, the UN High Commissioner for Refugees estimated 36 million people had been displaced by natural disasters and climate change.

In 2012, an Asian Development Bank report estimated 42 million people were displaced by climate-related disasters in Asia alone.

Now scientists predict the number of climate refugees could hit 200 million by 2050.

That’s a problem, considering Earth is getting crowded. Refugees can’t simply uproot and stake a new claim in terra nova. They’ve got to squeeze into places that are already bursting at the seams, probably facing their own climate-related strains, and not feeling terribly neighborly.

Thankfully, it won’t happen tomorrow. Rising sea levels will take years to swamp Bangladesh, and California still has water left. Climate change is gradual, producing a steady stream of migrants whose numbers can, with some foresight, be absorbed and assimilated.

Climate-related disasters, however, are a different animal. When they hit hard enough and often enough to overwhelm infrastructure and support systems, people pack up and leave. Fast.

A year after Hurricane Katrina, for example, the worst-hit Louisiana counties had lost 385,000 people, or 39 percent of their total population, to migration. That despite state infrastructure to help the afflicted stay and rebuild their homes.

The bad news is, we’re in for more hurricanes, more tornadoes, more of all the variations on the “Mother Nature isn’t happy” theme. Between 2000 and 2009, there were three times more climate-related disasters than there were between 1980 and 1989, according to the New England Journal of Medicine. Google climate trends, and you’ll see this stat isn’t an anomaly. Track the rising economic costs of rebuilding after these disasters, and you’ll see it isn’t financially sustainable, either.

I think we’ve had the smallest taste of migrations to come. Climate scientists agree on a steady rise in climate-related disasters and have put big circles around the global areas expected to take the worst hit (FYI, Asia is ground zero). But nobody can predict exact events, when they’ll strike, where, how badly, if they’ll lead to infrastructure collapse, and how many people they’ll send packing. There are simply too many X factors at play.

We can, however, get a glimmer of the cultural chaos these global migrations could create. There are phenomena that mirror, in a small way, the effects we’re expecting if mass migrations become the norm. One example is international tourism.

Mass migrations and large-scale tourism do have a few things in common. A large number of people entering a region. A local host who needs to accommodate the masses. And an ebb and flow in numbers that can reflect refugees being processed to other countries or tourists leaving in low season.

The UN studied the effect of tourist “tidal waves” to destinations, and discovered four ways that local cultures were being knocked off their foundations:

- Commodification: Local rituals, practices, and sites are sanitized and commoditized to make them palatable to visitors in what is called “reconstructed ethnicity.” As a result, they lose their sacred or unique value to locals.

- Standardization: Tourists may come for a new experience, but they crave products they’re familiar with. Fast-food restaurants and international hotel chains, for example.

- Loss of authenticity and staged authenticity: Local practices, dress, and rituals are reconstructed for tourists. Like commodification, this robs the local culture of its authenticity and devalues it in the eyes of the locals.

- Adaptation to tourist demands: Local artisans are tapped to create artifacts that satisfy tourist tastes. Although it gives the artisans a sense of worth, cultural erosion results from the commodification.

This rings true, you might say, but only in the case of wealthy tourists “invading” poorer countries and using their dollars to unwittingly maim the local culture. Not so. Consider the cultural imbroglio created by Euro Disney:

Resistance in France has come from various constituencies. French intellectuals declared themselves against the very idea of a Disney park which is openly propagandistic in content and practice. The French government made specific requirements to ensure a degree of Europeanization of the park, and the employees and the public has done the rest. Two years into the park’s operations, it consistently failed to meet operating costs. It is not clear that the failure had to do with the public’s specific dislike of the park’s attractions, but what is clear is that neither the government nor the people were ready to tolerate an exclusive enclave, with its own rules and social customs. But whereas the Government put its emphasis on political symbols and the economic revenues, the employees and the public worried about accessibility and exclusion, autonomy, hierarchy and jurisdiction over the public realm.

One might also consider the reaction of wealthy Hong Kong residents to the tidal wave of mainland Chinese flooding the city:

Tourism has become a boon to the local economy, with visitors contributing more than 5 percent of the city’s GDP last year, yet it has started to put pressure on Hong Kong’s local community. The effects of the influx of tourists go even deeper than bad behavior—the spending preferences of mainland visitors have altered the city’s urban fabric and triggered feelings among locals that their culture and way of life are under threat.

It’s less about rich people foisting their culture onto poor people than it is about sheer numbers of outsiders threatening to overwhelm the local culture.

Climate migrants could trample the culture of host countries. What then?

While unrelenting migrations caused by climate disasters haven’t happened yet, all indicators say they will. And the sheer numbers of migrants could conceivably unsettle, or even trample, the culture of host countries. What then?

I predict three outcomes.

Homogenization

Euro Disney attempted a mash-up of French culture and American fantasy, creating a bland, homogenized picture everyone could digest. In the same way, both hosts and migrants could find the interesting, unique elements of their cultures washed away as everyone struggles to get along.

Hostility

As local cultures are overwhelmed, hosts will likely feel threatened. They’ll become hyperprotective of icons and rituals they hold dear. Unfortunately, this will likely kill the inflow of new ideas, causing the culture to calcify and stagnate.

Disconnection

Possibly the greatest damage will be the disconnection of generations. Young people—both hosts and refugees—will more readily embrace the new, and older people will cling to their own culture for comfort. This will spark generational conflict and alienation.

As a marketer, this is all uncharted territory.

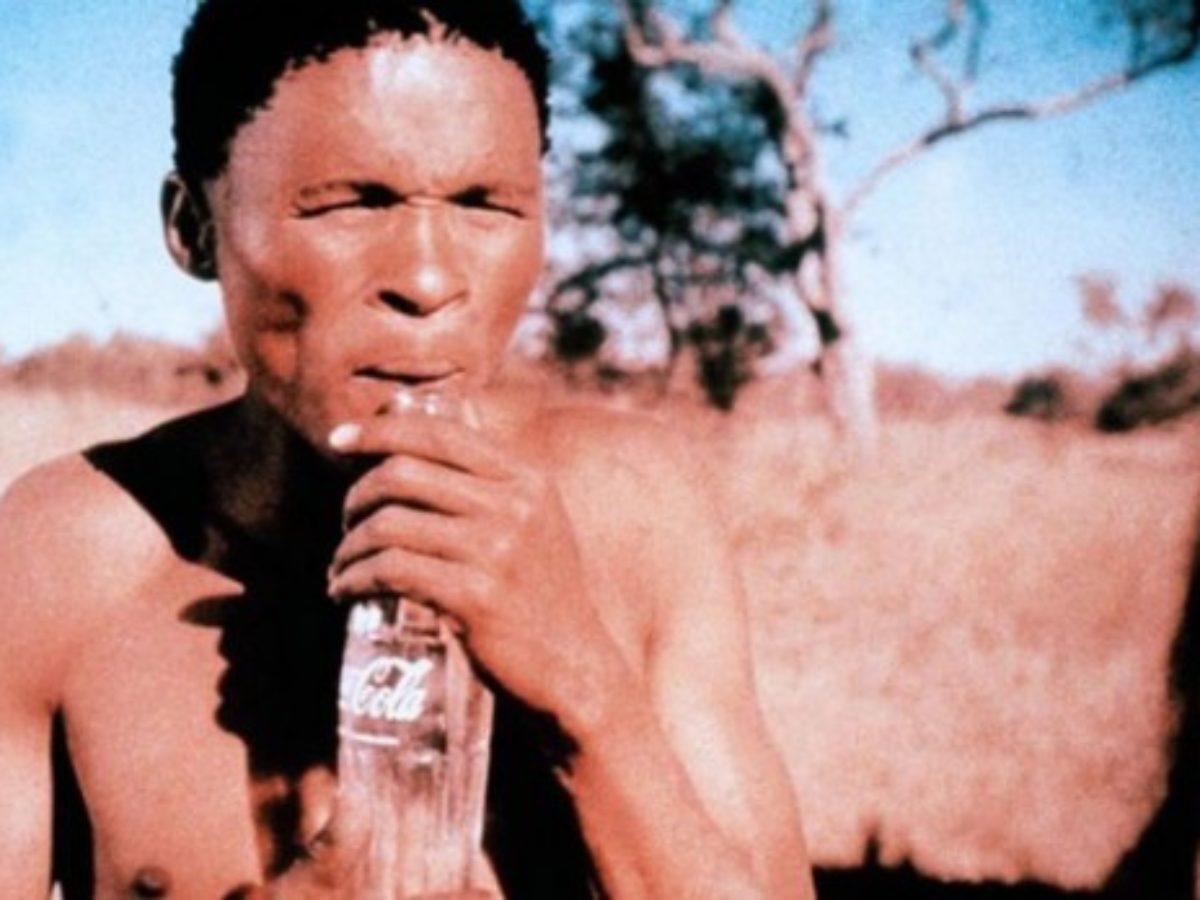

We could jump to obvious solutions—perhaps global brands will pull everyone together, so we can buy the world a Coke and keep it company. But this paints a superficial picture and ignores the complexity, confusion, and emotional charge of the situation.

We can segregate brands, making it about us versus them. But does this leave us stuck in time, unable to morph as the cultures evolve (or devolve)?

Or we can keep an open mind, reminding ourselves this disorder is the new world order, and chaos is the source of incredible innovation. Precisely the sort of innovation that could help us create brands that work.

This story first appeared in Huffington Post February 3rd, 2015.